St. Gobnait’s Holy Well – Ballyvourney

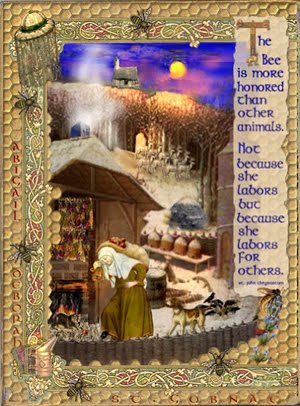

St. Gobnait – image by Patricia Banker

In the early 6th century when Gobnait fled her home in County Clare, she went to Inis Oírr. We don’t know why she fled, only that she believed she would find refuge in the Aran Islands.

Legend states that an angel appeared to her there and told her that her place was not on Inis Oírr, and instructed Gobnait to go on a journey – to seek her true place of resurrection. “Go until you find nine white deer grazing” the angel told her. “It is there that you will find your place of resurrection.”

So Gobnait wandered about the southern coastal counties of Ireland – Waterford, Cork and Kerry – searching.

She saw three white deer in Clondrohid and followed them to Ballymakeera where she saw six more. But it wasn’t until she came to Ballyvourney to a small rise overlooking the River Sullane that she saw the nine white deer all together – grazing … just as the angel from Inis Oírr had prophesied.

She crossed the river and settled there. She founded a religious community for women, performed memorable – some say miraculous works, and it was there she died and was buried.

Thin Places Mystical Tour

St. Gobnait’s shrine and holy well are stops on our Places of Resurrection tour .

DEVOTION TO ST. GOBNAIT

February 11th is St. Gobnait’s feast day -the day her memorable life is celebrated. She is one of the few Irish saints that is not only remembered in her native region, but has been proclaimed by the Irish bishops to be a national saint. There are shrines and places of devotion to St. Gobnait in all the places she is believed to have stopped on her journey – including Inis Oírr. But Ballyvourney, where she carried out most of her ministry, is the place that draws the greatest number of pilgrims devoted to this saint.

Today there is an active church on the former monastic site. St. Gobnait’s grave and marked spots around the churchyard are places where pilgrims pause for devotion and reflection. It is here that they can do the “rounds” or turas, always moving in a clockwise direction – a tradition that has pagan roots.

One of the strongest mystical draws on this site is St. Gobnait’s Holy Well, with its arched entryway that takes the pilgrim into a deeply shaded path. Just next to the well is a sturdy tree, and hanging from it are hundreds of tokens or clooties that have been placed there by pilgrims hoping to leave behind a part of themselves or loved on in need of healing. There are taps and cups available for drinking from the well or for pouring into personal vessels to take holy well water home.

Entrance to St. Gobnait’s Holy Well

St. Gobnait was best known for her care of the sick. There is a legend that tells of her staving off the plague from Ballyvourney by drawing a line in sand with a stick and declaring the village “consecrated ground.” Inside the church today, there is a medieval (possibly 13th century) figure of St. Gobnait which is kept in a drawer. Every year on her feast day, the parish priest brings out the figure to celebrate a devotional tradition. He holds up the ancient figure and the faithful each step forward with a piece of ribbon. They hold the ribbon up and measure it against the length and around the circumference of the figure, then take it home as a blessed relic used for healing or further devotion.

A tall statue of St. Gobnait that was erected in the 1950s stands near the monastic site. She appears with a nun’s habit standing on a bee hive surrounded by bees. Gobnait is the patron saint of bee keepers, and there are several legends recalling Gobnait forcing invaders out of Ballyvourney by setting swarms of bees upon them. It’s probable that Gobnait had a close relationship with bees and used honey in healing efforts.

Statue of St. Gobnait at Ballyvourney

PLACE OF RESURRECTION

Dan and I visited St. Gobnait’s monastic site many years ago. It is indeed, a thin place. The stories of St. Gobnait specifically mention a “place of resurrection.” I heard Dara Molloy use this phrase when referring to his home on Inis Mór and have seen a few authors reference the phrase. But regarding thin places … a place of resurrection is the pinnacle – that place where one’s spirit is totally whole, at home, with no longing or yearning to be anywhere else. A place of resurrection is not only the place where one’s spirit will resurrect from its lifeless body upon death, but also the place where that spirit is most alive inside the living body. And I believe that a place of resurrection is the spiritual home where one is most completely alive and able to create, to discern, to prophesy … to be wise.

Tree at St. Gobnait’s Holy Well – Ballyvourney, Co. Cork

The connection between the eternal world and the physical is nearly unidentifiable in a place of resurrection – as they are knitted together in an inextricable pattern where neither can be separated from the other. The place of resurrection then is unto itself the combination of both worlds particularly suited to that specific spirit. … and Ballyvourney was St. Gobnait’s place.

What is yours?

Image of St. Gobnait courtesy of Patricia Banker; Copyright by Patricia Banker, All Rights Reserved. Used With Permission.

Kildare – St. Brigid’s Holy Well (Tobar Bride)

Legend tells us that St Brigid was born near Kildare to a slave mother who was a Christian and very sickly. As a child, Brigid persuaded the Druid master to free her mother which in turn freed Brigid to enter religious life.

Legend tells us that St Brigid was born near Kildare to a slave mother who was a Christian and very sickly. As a child, Brigid persuaded the Druid master to free her mother which in turn freed Brigid to enter religious life.

Kildare is one of the stops on the Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland – Castles, Saints & Druids in September 2014.

Since there were no convents in Ireland, Brigid began one in Kildare. The sisters of St. Brigid prayed simply and deeply and served the poor. We know that Brigid was a contemporary of St. Patrick and a strong legend states that she was ordained a bishop because of her superior knowledge and closeness to God.

Another legend is associated with the goddess or holy woman, called Brigid dating back to pre-Christian times in this region. Stories of the two women have been woven and spun into legends and tales that all point to a holy woman, who drew followers to this site and performed rituals that were associated with healing, protection, comfort and help for the poor. The town of Kildare grew up around the community that this woman – Brigid – founded.

Kildare translated means “cell” or church of the oak. Oaks were known to be sacred trees in pre-Christian Ireland which gives weight to the pagan or goddess tradition of Brigid. But it is believed that a Christian woman named Brigid founded a community here around 480 AD, that she was a contemporary of St. Patrick and was recognized for great spiritual wisdom. There are legends that she was ordained a bishop in the church due to her wisdom.

Brigid is now one of Ireland’s patron saints, and is often linked in patronage to farmers and poor pastoral workers – the common citizen, the oppressed Irish tenant farmer of past centuries. It is possible – some say likely – that St. Brigid located her religious community on the spot where the Kildare Cathedral is now situated. 13th century buildings now occupy the spot along with the second tallest round tower in Ireland and an oratory and fire pit which likely date back to pagan times. Legend states that St. Brigid kept an flame burning in the fire pit continually as a devotion to the Holy Spirit. The perpetual flame is still cared for today by the Brigidine sisters who live nearby. For centuries this cathedral site has been a draw for pilgrims – a holy place, a place of spiritual strength.

Nearby is St. Brigid’s Holy Well, and the thinness of this place is palpable. This is actually a secondary well, springing from a known ancient holy well a short distance away. Volunteers and benefactors have created a beautiful setting around St. Brigid’s Holy Well also known as Tobar Bride. A bronze statue of St. Brigid lifting the eternal flame has been added in recent years. Stone prayer stations lead from the well to a running spring.

Wells were considered holy by the pre-Christian Irish being that they sprung from the “underworld” or the womb of the earth. That tradition of holiness exists today. Water from holy wells is believed to have special power for healing and spiritual protection.

“A holy well is very special. To watch water springing from the earth is to witness creation in the act of pure, unconditional generosity. At a holy well, my own interior holy well has an opportunity to make itself known to me.” – Gay Barbizon, Brigid’s Kildare; The Fire, the Well and the Oak.

Upon entering Tobar Bride, the pilgrim can see a small devotional shrine where donations are publicly accepted and welcomed. The old pagan tradition encourages the pilgrim to leave an offering when taking water from the well.

Pilgrims are encouraged to say prayers at each of the seven stations at Tobar Bride. Just past the small devotional shrine is the spring marked by a stone arch. This is the first station. Water flows through two oval shaped stones. Some say these stones symbolize the breasts of the earth – our mother. The bronze statue of St. Brigid is near to the arch.

Past the arch are five standing stones or “stations” that represent a part of Brigid’s nature. Pilgrims pause and recognize these qualities and perhaps pray for the same graces to develop in their own lives.

First stone – Brigid the woman of Ireland, the patroness, the protector of a beloved country.

Second stone – Brigid the peacemaker, healing division, bringing forward unity.

Third stone – Brigid the friend of the poor, advocate of the marginalized, speaker for they that have no voice.

Fourth stone – Brigid the hearthwoman, keeping the home flame burning, welcoming all, woman of hospitality.

Fifth stone – Brigid the woman of contemplation, which leads to wisdom and closeness with the Creator.

St. Brigid’s Holy Well – Kildare

The holy well behind the five standing stones marks the 7th station. It is here that one can pause and reflect, pray for a loved one, and draw water – perhaps to take to a loved one who is ill or to bless a home.

It is traditional belief that a person taking something from (holy water) from a devotional site should leave something behind. Notice the tree behind the well. Dangling from its branches are stips of cloth and other tokens – also known as “clooties” – that have been left behind by pilgrims. The cloth may have been touched to the person for whom the pilgrim is praying. Sometimes pilgrims leave photos or personal belongings behind – things that have touched the person they are praying for. This tree had a baby’s shoe dangling from a branch.

The pastoral setting of this park-like devotional space is near the Curragh – or places where the thoroughbred race horses – famous in Kildare – run and are kept. It is almost impossible not to be moved when entering this space.

This is a very Thin Place.

St. Columba and Glencolumbkille

Glencolumkille is a rural parish in southwest County Donegal. It is most known for its pilgrimage that honors the patron saint and protector of Donegal, St. Columba. There are many variations of his name (Columbkille, Colmcille). The Pilgrimage of St. Colmcille, also known as the Turas Cholmcille honor the saint while personally drawing his blessing and strength by walking in his footsteps across a land that was once his home. There are 15 stations scattered throughout an enchanted glen – each marked by a pillar stone or cairn or some type of stone marking.

Glencolumkille is a rural parish in southwest County Donegal. It is most known for its pilgrimage that honors the patron saint and protector of Donegal, St. Columba. There are many variations of his name (Columbkille, Colmcille). The Pilgrimage of St. Colmcille, also known as the Turas Cholmcille honor the saint while personally drawing his blessing and strength by walking in his footsteps across a land that was once his home. There are 15 stations scattered throughout an enchanted glen – each marked by a pillar stone or cairn or some type of stone marking.

My favorite definition for “pilgrim” was written by Paul Elie, found in his book The Life You Save May Be Your Own, a book about great writers and the power they have over us. Paul says, “A pilgrim travels within the context of a story, in order to be changed by the story.” The definition certainly fits the pilgrims who do the Turas in Glencolumkille.

To remember the story of St. Columbkille is to remember a man who was a descendent of the ruling tribe – royalty in his day. A man who was educated and tutored by the best scholars. Columbkille was a leader who could shape meaning from circumstances. He founded more monasteries and monastic communities than any other single Irish saint. But pride got the best of him when he was at his most powerful, and he picked an fight with another saint – St. Finian who had an illustrated psalter. St. Columbkille secretly copied St. Finian’s book so that he would have a copy for himself.

St. Finian was offended and demanded Columbkille’s copy. Columbkille refused saying knowledge gained from books should be shared not coveted, especially when pertaining to God. Finian took the matter to the High King for arbitration and the High King ruled in favor of St. Finian with a famous statement – “To every cow its calf and to every book it’s copy” meaning every calf belongs to its mother and every copy of a book belongs to the original book’s owner. Columbkille was outraged in losing the battle and this disagreement eventually led to Columbkille’s tribe attacking a tribe to the south which led to the slaughter of over 3000 people.

Columbkille was so ashamed to have been the root of so much death and destruction in his native land, that he sent himself into voluntary exile. He sailed from his beloved Derry to Scotland landing with a few followers on the island of Iona where he established a community which flourished into a great seat of learning and spiritual growth. Iona still has a community there and it continues today to draw pilgrims.

So as the pilgrims travel through the station in Glencolumbkille, they reflect on the saint’s life, his strength, his weaknesses and his devotion, and they ask his blessing for own lives. Every station has a ritual, a prayer to be said, a devotion to be made. So that when the turas are all done, the pilgrim has drawn strength from both the story and energy of the land.

The land has been considered sacred for thousands of years. Devotion and ritual in the glen dates back thousands of years. Portal tombs dating from 2000 BC can be found in the glen as well as court tombs the date to 4000 BC. The land in Glencolumbkille has an energy that early civilizations felt … that has lasted until the present day.

The land has been considered sacred for thousands of years. Devotion and ritual in the glen dates back thousands of years. Portal tombs dating from 2000 BC can be found in the glen as well as court tombs the date to 4000 BC. The land in Glencolumbkille has an energy that early civilizations felt … that has lasted until the present day.

Though Ireland has suffered in recent years with abuses committed by Catholic clergy which has rocked the faith of many, there are still hundreds that come to the glen each year to do the rounds. This kind of joining of devotion, spirit, land and healing never betrays trust.

I visited Glencolumbkille shortly after I married my husband. Our favorite spot was the Stone of Gathering (Turas 9). This tall carved pillar has a hole in the top. The stone was tied to a tradition where engaged couples would intertwine their fingers in the hole while professing their love and commitment to each other before a gathering of community members. There is also a tradition that if you peer through the hole (as Dan is doing in the image above) you will get a glimpse of heaven. The view from where Dan is standing is breathtaking. There is a special energy around this pillar… a kind of loving, warm, peaceful energy.

At the southwestern tip of Glencolumbkille is Slieve League (Sliabh Liag) which is the highest cliff face in Western Europe. The monastic serenity that blankets the entire glen and its scenic surroundings moves from peaceful to powerful – back and forth – and the prayers of the pilgrim mirror that energy.

“…echoes of the centuries’ feet

That moved along the penitential stones

In all thy winds are sweet.

Here came my fathers in their life’s high day

In barefoot sorrow, but God knows the whole:

Not for themselves they fasted, but to lay

Up riches for my soul.”

Glencolumkille and Slieve League are stops on the 2013 Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland. Check out the itinerary.

Other Good Webpages on Glencolumbkille and the Turas

Voices from the Dawn – Glencolumbkille Turas

Megalithic Ireland – Glencolumbkille Turas

Timoleague – Mystical Ruin on the Sea

Along the road between Kinsale and Clonakilty, near Courtmacsherry is the village of Timoleague which is dominated by the great seaside abbey ruin, a remnant of a 13th century Franciscan Friary. The abbey is built on the site of a former monastery founded by St. Molaga in the 7th century. Timoleague means – “house of Molaga.”

St. Molaga, as the story goes was a local boy who went to study the rule of St. Columba in Iona and then went on to Wales where he became good friends with St. David. He returned to Ireland and founded several monastic communities, but Timoleague was his greatest – and his last. He died here – probably of the plague. He and his followers were committed to helping those suffering from the disease when the plague hit Ireland in the late 7th century.

A story is told about how St. Molaga originally wanted to build his monastery farther up the estuary. But as he and his followers labored on the buildings by day, they all collapsed by night. St. Molaga took this as a sign that the Lord did not approve of the location. So he blessed a candle, lodged it in a rolled up sheath, set it alight and released it on the bay praying that God would help him find the perfect location for his new religious community. The candle floated until it stopped at the where the Timoleague ruin now stands. St. Molaga built his monastery on the sea and six hundred years later the Franciscans built an abbey on the foundations of St. Molaga’s monastery. The ruins of that monastery are what visitor’s see today.

I found this thin place through the recommendation of Mr. Noel O’Connor who was my host at Ashgrove Bed and Breakfast in Bandon. Over breakfast I asked him, “What is the most mystical place around here?” He was caught off-guard and hesitated. As a forma garda (police officer) I suspect he wasn’t invited to discuss “mystical” or thin places often. After pausing to give it some thought, he told me that many pilgrims go to Timoleague to pray and reflect. So I took his advise and I went to Timoleague.

What remains is a beautiful ruin now made into a comfortable public space on the scenic Courtmacsherry Harbor. When the monastery was active, boats used to sail right up to abbey, and the village grew around the activities focused there. Past the picnic tables and the stone wall are bones of the old religious house with haunting traces of how life existed there so many years ago.

Two favorite spaces for me were the dining room and the cloister walk. Pictured above is the cloister garth the part of a corner wall still standing. Monasteries typically had these square cloister walks with an open court-yard type garth in the center. The walks were the center of the the cloister and often used for doing “rounds” or walking and praying in a circular path. The walls bordering the garth had gothic-style windows to look out. I love to trace the steps of those who once walked and prayed here. On account I read said that at one corner of the walk the incorrupt body of a monk buried centuries before was discovered. He was reinterred on the grounds.

Another peaceful spot here is the refectory or dining area. It’s a large rectangular room off the back of the ruin with five tall windows (frames still in tact) looking out over the sea. Next to this area is a cavity wall, with indentations known as the fairy cupboards. It was from this room that children discovered an ancient book buried under one of the flagstones. They destroyed it and only the shred of the cover was found.

In the sacristy is the ancient holy water font, now known as the Wart Well. It is said to heal warts when those afflicted dip the warts into the water.

The monastery was sacked in the 1600s and three monks escaped by boat and took with them the Timoleague chalice for safe keeping. It was discovered in an old box in a home in the village many years ago and is now held by one of the priests residing in Timoleague.

In the distance behind the ruin a round tower (new) can be seen atop a church. This is the Catholic Church dedicated to the Nativity of the Blessed Mother. One of Henry Clark’s last stain glass masterpieces can be found here.

Timoleague is a haunting site full of mystery and charged with the energy of the past. It is one of the stops on the Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland in May of 2011.

Holy House of ivied gables

That wert once the country’s pride

Houseless now in weary wandering

Roam your inmates far and wide

~from Lament Over the Ruins of the Abbey of Timoleague

John Collins -1814

Mount Brandon – Named for St. Brendan

St. Brendan, one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland, was a holy man and a navigator. He was born and raised in the Dingle area, and ordained a priest in 512 AD. Brendan was founder of several monastic settlements in Ireland, one being at the base of of a great mountain on Dingle’s north shore – now known as “Mount Brandon.”

The mountain was named after the famous St. Brendan, perhaps because he founded a monastic community here, or more likely because it was from the base of this mountain that St. Brendan launched his fleet of curraghs, filled with his followers, to set out on a seven year spiritually guided journey to find the “promised land” – the Isle of the Blest.

Legend states that St. Brendan climbed to the peak of Mount Brandon, looked across the Atlantic and saw the Americas. Many believe that Brendan reached North America way before Christopher Columbus, and several groups have alleged that Columbus referred to a manuscript that told of Brendan’s journey across the Atlantic. Much has been written about the Voyages of Brendan. What we know to be true is that Brendan grew spiritually on the journey and returned with the ability to draw large numbers into a deeper spiritual existence

St. Brendan is the patron saint of sailors and of travelers and is still reverenced in Ireland and around the Christian world. And the holy mountain, named for him, that dominates the northern landscape in Dingle is a reminder of where the journey began for a great spiritual leader, and where the journey begins – even today – for those that try to follow in his footsteps.

Brandon Head, the alleged launch site for Brendan and his followers, can only be accessed by foot. There is a pilgrim’s path that runs along the mountain that hikers and walkers traverse. The views from this trail are remarkable. But if you can’t take the walk, the views from Kilshannig, Castle Gregory or any of the strands off the northern road offer tremendous views. Often, the peak of Mount Brandon is hidden in the clouds.

Mount Brandon is a thin place. I had one of the strongest touches from the other world on a strand facing Mount Brandon. That story may come in another post.

Flickr photos for Mount Brandon.

St. Brendan’s Prayer

Shall I abandon, O King of mysteries, the soft comforts of home? Shall I turn my back on my native land, and turn my face towards the sea?

Shall I put myself wholly at your mercy, without silver, without a horse, without fame, without honour? Shall I throw myself wholly upon You, without sword or shield, without food and drink, without a bed to lie on? Shall I say farewell to my beautiful land, placing myself under Your yoke?

Shall I pour out my heart to You, confessing my manifold sins and begging forgiveness, tears streaming down my cheeks? Shall I leave the prints of my knees on the sandy beach, a record of my final prayer in my native land?

Shall I then suffer every kind of wound that the sea can inflict? Shall I take my tiny boat across the wide sparkling ocean? O King of the Glorious Heaven,

shall I go of my own choice upon the sea?

O Christ, will You help on the wild waves?

The Rock of Cashel – St. Patrick’s Rock

The Rock of Cashel Rises from the Golden Vale

The Pre-Christian and Celtic people of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England had a keen sense for thin places. The landscape in these countries is littered with man-made markings and ruins that remind the passer-by that this is holy ground. The rocks, trees and landscape hold the memories of spiritual exercises here long ago and present.

Cashel is a thin place.

The very ground itself seems to call out, “Come here and be transformed.” In a quiet moment, the pilgrim today can sense a connection with the souls that have marked these spots with their spirits. Cashel is a vivid reminder that we are all joined inside and outside of time.

The Tipperary Plain also known as the Golden Vale, spreads like a quilt of green and gold velvet patchwork, delineated by hedgerows, lines of trees and occasional roadway, and framed by distant Slieve Bloom Mountains. It’s called the Golden Vale because of the rich, fertile soil which brought prosperity to those who farmed it. Out of the center of the Vale, rising some 200 feet is the Rock of Cashel.

Crowned with the ruins of 11th and 12th century buildings, the Rock is woven into a series of legends, all associated with power and dominance that span nearly two thousand years. The Rock is also referred to as “the Devils Bit.” According to Irish legend, the devil was flying home (presumably to England) when in a fit of anger he bit off a piece of the Slieve Bloom Mountains and spewed it out into the middle of the Tipperary Plain, creating the Rock of Cashel. There is a unique “vacancy” in the hills around Cashel that looks decidedly like a bite. But the Slieve Bloom are comprised of sandstone and the Rock of Cashel of limestone, so the Devil’s Bit theory is unlikely.

St. Patrick’s Rock

Legend states that St. Patrick preached here in the fifth century. He came to convert King Aengus and baptized the King around 450 AD. Patrick later made Cashel a bishopric claiming it as a seat of power long before it was the seat of the high kings of all Ireland.

In the twelfth century, a high cross, now known as “St. Patrick’s Cross,” was erected at Cashel to commemorate 800 years since St. Patrick’s visit. The original cross is quite weathered, but the image of the crucified Christ on the west face and the image of a man (possibly St. Patrick) on the east face can still be made out. The cross rests on a massive base repudiated to be the coronation stone of the Kings of Muenster. A replica of the cross and base greets visitors as they enter the enclosure on the Rock. The original cross and base are in the museum – also known as the Hall of Vicars, which also serves as the Visitor’s Center.

In the twelfth century, a high cross, now known as “St. Patrick’s Cross,” was erected at Cashel to commemorate 800 years since St. Patrick’s visit. The original cross is quite weathered, but the image of the crucified Christ on the west face and the image of a man (possibly St. Patrick) on the east face can still be made out. The cross rests on a massive base repudiated to be the coronation stone of the Kings of Muenster. A replica of the cross and base greets visitors as they enter the enclosure on the Rock. The original cross and base are in the museum – also known as the Hall of Vicars, which also serves as the Visitor’s Center.

The Rock, called Cashel of the Kings – Cashel is Irish for stronghold – dominates the surrounding landscape, its drama unparalleled in Ireland, and its history is every bit as dramatic. For one thousand years it was the seat of power for Irish kings and bishops, ruling the surrounding country, and for a time, the entire country. For 400 years it rivaled Tara as the seat of power for all of Ireland. The kings of Munster were crowned here and ruled from Cashel. In 978, Brian Boru declared himself High King of Ireland and was crown on the Rock of Cashel. He made Cashel his capital. Brian Boru was the first to unite all of Ireland with its centuries-long history of warring clans and tribes. He was also the last to unite all of Ireland, for since his death in 1014, no one person has unified the populations in all four provinces.

Boru’s descendants ruled from Cashel for one hundred years after his death when Murtagh O’Brien in 1101 gave the Rock of Cashel to the Catholic Church and it began to thrive as a Cathedral.

In 1647 the Earl Inchquin (under Cromwell’s influence) plundered the city. The townspeople fled to the Rock for safety and barricaded themselves in the Cathedral. Inchquin’s army piled turf around the cathedral and set it afire. All inside were burned to death. Over 800 people perished under that attack. The Rock was later abandoned, left to fall further into ruin. Finally, in 1874 it was declared a national monument and since then has been lovingly restored.

I will never forget the first time I saw the Rock of Cashel.

At 10:00 a.m. we came down the Tipperary Road into Cashel. Seeing the Rock emerge from the landscape stirred childhood memories of seeing Emerald City rise up at the end of the yellow brick road in the Wizard of Oz. It was a moment when time stood still, burned in my memory like a trauma or birth.

At 10:00 a.m. we came down the Tipperary Road into Cashel. Seeing the Rock emerge from the landscape stirred childhood memories of seeing Emerald City rise up at the end of the yellow brick road in the Wizard of Oz. It was a moment when time stood still, burned in my memory like a trauma or birth.

That day we climbed the Rock of Cashel and wandered through the Cathedral ruins and cemetery. I knew nothing then about the history, who lived there, who ruled from there, what events took place there, but I knew it was a thin place. There was something exhilarating about Cashel, an excitement, a sense of power.

Cashel has long been linked with power. Warriors, chieftains, kings, princes, saints and bishops have all come here to mark the Rock as the seat of power, and blood has been spilled in that struggle for power. The Rock is not a peaceful place – as its legacy is riddled with memories of those who fought for power, stole power, ran to take refuge under the mantle of the powerful, and those who gloriously won the power.

The thinness is palpable. Your spirit is awake at Cashel.

I have returned to the Rock of Cashel with every visit to Ireland. I have seen the Rock lit up at night, covered in rain and mist, set against the frigid winter landscape and lingering through the long days of summer where the sun barely sets before rising again.

The Rock of Cashel, though in ruin, has a constancy; a historic brilliance that defies the modernization that grows around it with new homes, buildings and roadways. Cashel boldly claims her history, memories of kings, chieftains, warriors, bards, and holy men – thrusting them before us, urging us to enter in to her ancient legacy – and to return, and return and return.

So many people ask me, “What should I see on my visit to Ireland?”

I always say, “Don’t miss the Rock of Cashel.” Sadly, only a few heed my suggestion.

What a pity.

They’ll never know what I know… that Cashel will seduce you like a lover and cling to your spirit, planting some small charm that draws you back to her, creating a hunger for reunion. With each visit your are strengthened and sustained … until the next time. Cashel is like a first love. Though time, distance and life experience may stand between you – you never forget her, and you will return to her over and over in your imagination. You are changed forever for having known her.

Ardmore in County Waterford – the Oldest Christian Settlement in Ireland

Ardmore is a fishing village in County Waterford – just over the border from County Cork. It is the legendary home of St. Declan who is said to have settled there somewhere between 350 and 420 AD, bringing Christianity to the island even before St. Patrick. If this is true, it makes Ardmore the oldest Christian settlement in Ireland.

Ardmore from the Irish “Aird Mhor” means great height. The ruins of a 13 century church, an 8th century oratory and a well preserved 12th century round tower dominate a hillside overlooking Ardmore Bay, a fitting spot for Ireland’s first monastic community.

Driving up the hillside one sees the 90 foot round tower rear up from the landscape like some old relic. That’s when the “thinness” of the place starts to sink in. Come closer and the ruins of St. Declan’s Church with its carved religious scenes – Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Judgment of Solomon, the Visit of the Magi – emerge from the ancient landscape. The scenes were used to help teach the local community about the Christian faith. This carved church wall is three hundred years older than the church itself, dating the carvings to the 9th century. The wall was actually brought to the site from another ruined religious site that had fallen into decay, so this spot on the hill at Ardmore is its second home.

Almost unnoticeable is the small 8th century oratory built over the spot where St. Declan is believed to be buried. It lies just below the ruined church – hemmed in by graves, both old and recent. Headstones and grave markers occupy nearly every bit of available ground space around the ruins. Some new shiny granite, some old limestone with faded inscriptions, and some merely jagged stones set atop a lump.

The wild beauty of the landscape around the monastic site is mirrored on the nearby cliffs where a pilgrim’s walkway has been carved out. The path leads to the village and St. Declan’s holy well.

Remnants of by-gone spiritual hunger and discovery still cling to the old ruins at Ardmore. The stones hold the memories of faith, of sorrow, of devastation, of joy, of celebration. It is the presence of those memories stored in the ruins that dissolves the veil separating the past, present and eternal worlds. All are knitted together and the elements – the sky, the wind, the sea, the stones – seem brighter, and somehow more vivid.

Ardmore is a thin place, and is on our Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland this September. Come join us.