What’s the Deal With Thin Places?

In a a phone interview last week, I was asked, “What’s the deal with thin places?” I was being interviewed by a journalist covering business, and the focus of the article was to be using social media to grow a business. But the interviewer had done some background research on me, read my blogs and seen that I write about, give lectures on, and gives tours of “thin places.”

So I gave the writer my standard answer, “thin places are places where the veil between this world and the eternal world is thin.” The look on his face said, “So?”

I continued, “Do you really want to get into this?” He said, “Why not?” I found myself regurgitating the same old stale sentences I’ve used in the past, perhaps because I assumed this business journalist had no genuine interest in the concept of mystical sites. However, his confused face betrayed his business focus and revealed a personal intrigue. He said, “Why would I want to go to a thin place?”

Hmmm. Why would he?

I offered an explanation, and soon found my raised voice and overt hand gestures revealing my passion for thin places. I tend to lose control.

My answer to “Why would I want to go to a thin place?”

We humans are physical, mental and spiritual. Our spiritual side, unlike the physical and mental side is not experienced through our five senses. All civilizations have left behind indications that they had a spiritual life, that they looked beyond the physical world and communicated with the eternal world.

If meat and veggies feed the body, and books and learning feed the mind, thin places feed the soul and help to expand the human spirit. A place with an inherent mystical quality or “thin veil” between worlds allows the person in that place to stretch and grow his or her spiritual sensitivities. These places help us pray better, contemplate on a deeper level, and “touch the other side”… manifesting the power of the eternal world inside ourselves.

Grace and spiritual blessings come easily in thin places. Insights emerge and amaze us. Answers to spiritual questions are heard. And the greatest of all spiritual endowments is magnified in thin places – inner peace.

Peace.

Worries are diminished, depression lifted, and priorities redefined when we expand our degree of inner peace, and our gratitude for simple things is amplified. Inner peace enlarges our sense that all nature is charged with divinity, a common theme over the centuries – evident in Psalm 148 and St. Francis of Assis’s Canticle of the Creatures.

Is there value in that?

Thin Places – Do we make them thin or are they inherently thin?

I’m a believer that thin places are inherently thin, and their mystical qualities draw humans to them. And though I believe that thin places exist all over the planet, I don’t believe we – that is humans – make these places thin by connecting with God there. Perhaps great acts of humans living, loving, suffering, or dying in a particular place impact the veil – thus the thinness in places like Gettysburg, Thoor Ballylee, Taj Mahal, or Skibbereen. But a thin place is what it is. In most cases, we don’t impact the degree of thinness. Keen, spiritual sensitivities help us identify these places.

I reject the idea that we create our own thin places. “Because I feel God’s presence strongly right now, this must be a thin place.” I believe that with a well exercised spirit we can enter into a spiritual state more readily – anywhere. That same exercised spirit will also be able to identify a place that is mystical and close to the eternal, and take advantage of the openness.

Blessings Come to Us in Thin Places

When the human spirit is tuned in at a thin place, communication with the eternal world flows back and forth readily and easily. Not just with God, but with the communion of saints – those that have gone before us. We all stand in the same time, in the same space. Our prayers joined with prayers of the saints makes our humble prayer stronger. Spiritual graces and insights flow. We find ourselves easily uncovering answers to the questions of the heart. We find encouragement for our sense of defeat, comfort for the losses we mourn.

I find the presence of love – the greatest power in the world – so prevalent in thin places that it is almost palpable. Love knows now barriers between worlds. It hovers in a thin place, unifying both the physical and the eternal. That overwhelming sense of the presence of spiritual love is worth the visit.

For me, these are worthy reasons for traveling to thin places.

Invite all you readers to come with us on the Thin Places Tour.

Mount Brandon – Named for St. Brendan

St. Brendan, one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland, was a holy man and a navigator. He was born and raised in the Dingle area, and ordained a priest in 512 AD. Brendan was founder of several monastic settlements in Ireland, one being at the base of of a great mountain on Dingle’s north shore – now known as “Mount Brandon.”

The mountain was named after the famous St. Brendan, perhaps because he founded a monastic community here, or more likely because it was from the base of this mountain that St. Brendan launched his fleet of curraghs, filled with his followers, to set out on a seven year spiritually guided journey to find the “promised land” – the Isle of the Blest.

Legend states that St. Brendan climbed to the peak of Mount Brandon, looked across the Atlantic and saw the Americas. Many believe that Brendan reached North America way before Christopher Columbus, and several groups have alleged that Columbus referred to a manuscript that told of Brendan’s journey across the Atlantic. Much has been written about the Voyages of Brendan. What we know to be true is that Brendan grew spiritually on the journey and returned with the ability to draw large numbers into a deeper spiritual existence

St. Brendan is the patron saint of sailors and of travelers and is still reverenced in Ireland and around the Christian world. And the holy mountain, named for him, that dominates the northern landscape in Dingle is a reminder of where the journey began for a great spiritual leader, and where the journey begins – even today – for those that try to follow in his footsteps.

Brandon Head, the alleged launch site for Brendan and his followers, can only be accessed by foot. There is a pilgrim’s path that runs along the mountain that hikers and walkers traverse. The views from this trail are remarkable. But if you can’t take the walk, the views from Kilshannig, Castle Gregory or any of the strands off the northern road offer tremendous views. Often, the peak of Mount Brandon is hidden in the clouds.

Mount Brandon is a thin place. I had one of the strongest touches from the other world on a strand facing Mount Brandon. That story may come in another post.

Flickr photos for Mount Brandon.

St. Brendan’s Prayer

Shall I abandon, O King of mysteries, the soft comforts of home? Shall I turn my back on my native land, and turn my face towards the sea?

Shall I put myself wholly at your mercy, without silver, without a horse, without fame, without honour? Shall I throw myself wholly upon You, without sword or shield, without food and drink, without a bed to lie on? Shall I say farewell to my beautiful land, placing myself under Your yoke?

Shall I pour out my heart to You, confessing my manifold sins and begging forgiveness, tears streaming down my cheeks? Shall I leave the prints of my knees on the sandy beach, a record of my final prayer in my native land?

Shall I then suffer every kind of wound that the sea can inflict? Shall I take my tiny boat across the wide sparkling ocean? O King of the Glorious Heaven,

shall I go of my own choice upon the sea?

O Christ, will You help on the wild waves?

Drive Around Dingle – Slea Head

One of the most scenic drives in Europe is the Dingle drive around Slea Head – the western tip of the Dingle Peninsula where glimpses of Slea Head and the Blasket Islands provide stunning sea views.

One of the most scenic drives in Europe is the Dingle drive around Slea Head – the western tip of the Dingle Peninsula where glimpses of Slea Head and the Blasket Islands provide stunning sea views.

My favorite part of the drive is just past the Great Blasket Center. Across the water on sees the “Sleeping Giant” – an off-shore island that looks remarkably like a giant stretched out on his back with hands resting across his stomach.

Nearby on the hilly ground on the land-side of the road are abandoned potato farms, left when the blight hit, never to be reclaimed. Whether sunny, cloudy or pouring rain, the Slea Head drive offers the traveler or pilgrim a peaceful, scenic look that has been relatively unchanged for centuries.

Slea Head is marked by a life-size white crucifix with Mary and St. John standing by. It appears incredibly stark in contrast to the gray rock and earth behind it and the blue / white surf below it. The white statues stand out, identifying Slea Head to the fisherman, and on a clear day- even some islanders can catch a glimpse.

The Rock of Cashel – St. Patrick’s Rock

The Rock of Cashel Rises from the Golden Vale

The Pre-Christian and Celtic people of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England had a keen sense for thin places. The landscape in these countries is littered with man-made markings and ruins that remind the passer-by that this is holy ground. The rocks, trees and landscape hold the memories of spiritual exercises here long ago and present.

Cashel is a thin place.

The very ground itself seems to call out, “Come here and be transformed.” In a quiet moment, the pilgrim today can sense a connection with the souls that have marked these spots with their spirits. Cashel is a vivid reminder that we are all joined inside and outside of time.

The Tipperary Plain also known as the Golden Vale, spreads like a quilt of green and gold velvet patchwork, delineated by hedgerows, lines of trees and occasional roadway, and framed by distant Slieve Bloom Mountains. It’s called the Golden Vale because of the rich, fertile soil which brought prosperity to those who farmed it. Out of the center of the Vale, rising some 200 feet is the Rock of Cashel.

Crowned with the ruins of 11th and 12th century buildings, the Rock is woven into a series of legends, all associated with power and dominance that span nearly two thousand years. The Rock is also referred to as “the Devils Bit.” According to Irish legend, the devil was flying home (presumably to England) when in a fit of anger he bit off a piece of the Slieve Bloom Mountains and spewed it out into the middle of the Tipperary Plain, creating the Rock of Cashel. There is a unique “vacancy” in the hills around Cashel that looks decidedly like a bite. But the Slieve Bloom are comprised of sandstone and the Rock of Cashel of limestone, so the Devil’s Bit theory is unlikely.

St. Patrick’s Rock

Legend states that St. Patrick preached here in the fifth century. He came to convert King Aengus and baptized the King around 450 AD. Patrick later made Cashel a bishopric claiming it as a seat of power long before it was the seat of the high kings of all Ireland.

In the twelfth century, a high cross, now known as “St. Patrick’s Cross,” was erected at Cashel to commemorate 800 years since St. Patrick’s visit. The original cross is quite weathered, but the image of the crucified Christ on the west face and the image of a man (possibly St. Patrick) on the east face can still be made out. The cross rests on a massive base repudiated to be the coronation stone of the Kings of Muenster. A replica of the cross and base greets visitors as they enter the enclosure on the Rock. The original cross and base are in the museum – also known as the Hall of Vicars, which also serves as the Visitor’s Center.

In the twelfth century, a high cross, now known as “St. Patrick’s Cross,” was erected at Cashel to commemorate 800 years since St. Patrick’s visit. The original cross is quite weathered, but the image of the crucified Christ on the west face and the image of a man (possibly St. Patrick) on the east face can still be made out. The cross rests on a massive base repudiated to be the coronation stone of the Kings of Muenster. A replica of the cross and base greets visitors as they enter the enclosure on the Rock. The original cross and base are in the museum – also known as the Hall of Vicars, which also serves as the Visitor’s Center.

The Rock, called Cashel of the Kings – Cashel is Irish for stronghold – dominates the surrounding landscape, its drama unparalleled in Ireland, and its history is every bit as dramatic. For one thousand years it was the seat of power for Irish kings and bishops, ruling the surrounding country, and for a time, the entire country. For 400 years it rivaled Tara as the seat of power for all of Ireland. The kings of Munster were crowned here and ruled from Cashel. In 978, Brian Boru declared himself High King of Ireland and was crown on the Rock of Cashel. He made Cashel his capital. Brian Boru was the first to unite all of Ireland with its centuries-long history of warring clans and tribes. He was also the last to unite all of Ireland, for since his death in 1014, no one person has unified the populations in all four provinces.

Boru’s descendants ruled from Cashel for one hundred years after his death when Murtagh O’Brien in 1101 gave the Rock of Cashel to the Catholic Church and it began to thrive as a Cathedral.

In 1647 the Earl Inchquin (under Cromwell’s influence) plundered the city. The townspeople fled to the Rock for safety and barricaded themselves in the Cathedral. Inchquin’s army piled turf around the cathedral and set it afire. All inside were burned to death. Over 800 people perished under that attack. The Rock was later abandoned, left to fall further into ruin. Finally, in 1874 it was declared a national monument and since then has been lovingly restored.

I will never forget the first time I saw the Rock of Cashel.

At 10:00 a.m. we came down the Tipperary Road into Cashel. Seeing the Rock emerge from the landscape stirred childhood memories of seeing Emerald City rise up at the end of the yellow brick road in the Wizard of Oz. It was a moment when time stood still, burned in my memory like a trauma or birth.

At 10:00 a.m. we came down the Tipperary Road into Cashel. Seeing the Rock emerge from the landscape stirred childhood memories of seeing Emerald City rise up at the end of the yellow brick road in the Wizard of Oz. It was a moment when time stood still, burned in my memory like a trauma or birth.

That day we climbed the Rock of Cashel and wandered through the Cathedral ruins and cemetery. I knew nothing then about the history, who lived there, who ruled from there, what events took place there, but I knew it was a thin place. There was something exhilarating about Cashel, an excitement, a sense of power.

Cashel has long been linked with power. Warriors, chieftains, kings, princes, saints and bishops have all come here to mark the Rock as the seat of power, and blood has been spilled in that struggle for power. The Rock is not a peaceful place – as its legacy is riddled with memories of those who fought for power, stole power, ran to take refuge under the mantle of the powerful, and those who gloriously won the power.

The thinness is palpable. Your spirit is awake at Cashel.

I have returned to the Rock of Cashel with every visit to Ireland. I have seen the Rock lit up at night, covered in rain and mist, set against the frigid winter landscape and lingering through the long days of summer where the sun barely sets before rising again.

The Rock of Cashel, though in ruin, has a constancy; a historic brilliance that defies the modernization that grows around it with new homes, buildings and roadways. Cashel boldly claims her history, memories of kings, chieftains, warriors, bards, and holy men – thrusting them before us, urging us to enter in to her ancient legacy – and to return, and return and return.

So many people ask me, “What should I see on my visit to Ireland?”

I always say, “Don’t miss the Rock of Cashel.” Sadly, only a few heed my suggestion.

What a pity.

They’ll never know what I know… that Cashel will seduce you like a lover and cling to your spirit, planting some small charm that draws you back to her, creating a hunger for reunion. With each visit your are strengthened and sustained … until the next time. Cashel is like a first love. Though time, distance and life experience may stand between you – you never forget her, and you will return to her over and over in your imagination. You are changed forever for having known her.

Skibbereen Famine Cemetery – a thin place

Abbeystrewery Cemetery in Skibbereen. 8000 – 10,000 victims of the Great Hunger are buried here.

Abbeystrewery Cemetery in Skibbereen. 8000 – 10,000 victims of the Great Hunger are buried here.

Skibbereen was a hub of commerce in southern Ireland during the nineteenth century, with the River Ilen flowing through the town ending at the Baltimore Harbour near the Atlantic Ocean. But Skibbereen is perhaps most famous for its association with the Great Famine that hit Ireland hardest in 1846-47. The song Skibbereenwith a haunting melody and lyrics that tell of a father recounting to his son the cruel reason why he left his beloved homeland “old Skibbereen,” – he lost the farm, the house, and he lost his wife to hunger when the boy was but 2 years old. So the father fled with the young son wrapped in his coat – never to return for fear of being imprisoned for the debt he owned in taxes and rent. County Cork was one of the areas in Ireland that lost over one third of its population to the Famine in those years.

History states that the Famine occurred because of a failure in the potato crop in Ireland. The Irish were under British occupation at the time. Rich landlords controlled the country, though they were a small portion of the population. Most of the population served as tenants to these landlords, and suffered from high rents and taxes. Poverty ran deep in the tenant class, which used the potato as the main staple of its diet. When the crop failed, panic set in. The Irish sold what they had, including boats and fishing equipment to feed their suffering families. One in three people died in the area surrounding Skibbereen. Most concur that there was plenty of food in Ireland – plenty enough to feed the starving citizens. But the food was exported for profit that was made by the British government and the Anglo Irish ruling class.

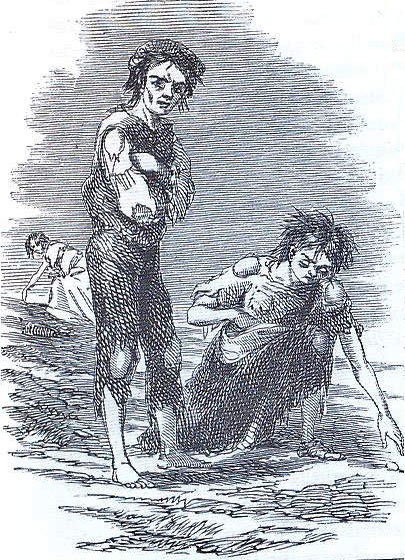

Sketch by illustrator James Mahony entitled – Skibbereen 1847 – Mahony produced this for a London newspaper in the same year

Sketch by illustrator James Mahony entitled – Skibbereen 1847 – Mahony produced this for a London newspaper in the same year

People were dying so fast in Skibbereen that there weren’t enough people alive to take care of the task of burying the dead. So a mass grave was dug near the ruins of the old Abbeystrewery Franciscan friary. It is estimated that 8,000 to 10,000 nameless, coffinless, unremembered dead were dumped into the mass grave. Today the lumpy plot of ground has green grass covering the burial site and a stone marker that says:

In Memory of the Victims of the Famine 1845-48

Whose Coffinless Bodies were Buried in this Plot

There is a commemorative Famine trail that begins at the town center and includes the Skibbereen Heritage Centre and the Abbeystrewery Cemetery (pictured above). The artistic renderings of stone cutters and poets that dapple the cemetery grounds with tokens of remembrance are worth a trip to Skibbereen. So much sorrow here. One can’t helped but be moved.

Skibbereen is a thin place. And it is a stop on our Thin Places Tour in September 2010.

Kilshannig – The North Side of Dingle Littered with Bones

Church Ruin sitting on Brandon Bay in Kilshannig

One of the few places in Ireland I can photographically remember is Kilshannig, a small dilapidated village on the Dingle peninsula at its northernmost point. Most visitors that spend a day or less in Dingle seldom visit the northern route which has spectacular sea views, beautiful sandy beaches and commanding perspectives of Mount Brandon.

Just past Castlegregory is the turn-off to go out toward Rough Point. Kilshannig is a hilly village with a few small houses and narrow roads. We found cows wandering freely on the roadside and most of the buildings looked vacant. St. Senan or Seanaigh built a monastery in the Magharee Islands just off the coast of this village in the 7th century that was accessed by sea. A 15th century (some say earlier) church ruin now occupies the site at the edge of village overlooking Brandon Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. This little church was the mainland church for the monastery on the island.

7th Century Cross Slab – Kilshannig

Inside the church walls is cross-pillar slab from the 7th century. It has a Greek style cross carved on it and has been white washed. There are similar carvings on pillar slabs in Glencolmkille in County Donegal. It’s believed that the slabs were part of a pagan ritual before the area was Christianized. This may have served as a wayside marker. No one really knows for sure what these standing stones represented.

What a remarkable experience to add one’s own hands to the collection of thousands that have traced the engraved path of the cross on that ancient stone.

Cary Meehan, author of A Traveller’s Guide to Sacred Ireland writes:

“In the graveyard is a cross pillar with a fine incised cross with expanded terminals and a double spiral at its base, similar to those at Kilfountain, Kilmalkedar, and Reask.”

Graveyard is Being Reclaimed by the Sea – Bones Everywhere

The ruined church was converted to a cemetery as were most of the church ruins in Ireland. And though the church was built on high ground above the sea, Brandon Bay has occasionally eclipsed the banks and invaded some of the old graves. Bones have washed out of the graves and litter the area in and around the church. While it was a somewhat macabre site for us, it was also a reminder that our remains join all the elements of nature eventually. We all return to dust.

We found some interesting green chards scattered in one place. They had no sharp edges, either glass shards worn down by the sea or some type of stone.

The views from Kilshannig are spectacular. Mount Brandon dominates the western view with Brandon Bay lapping up on a shoreline that extends nearly a half mile out to sea. In the distance, the crashing waves of the Atlantic Ocean can be seen and heard. The silence of the village – save for the wind and sea – is almost eerie. This is a holy place.

Ardmore in County Waterford – the Oldest Christian Settlement in Ireland

Ardmore is a fishing village in County Waterford – just over the border from County Cork. It is the legendary home of St. Declan who is said to have settled there somewhere between 350 and 420 AD, bringing Christianity to the island even before St. Patrick. If this is true, it makes Ardmore the oldest Christian settlement in Ireland.

Ardmore from the Irish “Aird Mhor” means great height. The ruins of a 13 century church, an 8th century oratory and a well preserved 12th century round tower dominate a hillside overlooking Ardmore Bay, a fitting spot for Ireland’s first monastic community.

Driving up the hillside one sees the 90 foot round tower rear up from the landscape like some old relic. That’s when the “thinness” of the place starts to sink in. Come closer and the ruins of St. Declan’s Church with its carved religious scenes – Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Judgment of Solomon, the Visit of the Magi – emerge from the ancient landscape. The scenes were used to help teach the local community about the Christian faith. This carved church wall is three hundred years older than the church itself, dating the carvings to the 9th century. The wall was actually brought to the site from another ruined religious site that had fallen into decay, so this spot on the hill at Ardmore is its second home.

Almost unnoticeable is the small 8th century oratory built over the spot where St. Declan is believed to be buried. It lies just below the ruined church – hemmed in by graves, both old and recent. Headstones and grave markers occupy nearly every bit of available ground space around the ruins. Some new shiny granite, some old limestone with faded inscriptions, and some merely jagged stones set atop a lump.

The wild beauty of the landscape around the monastic site is mirrored on the nearby cliffs where a pilgrim’s walkway has been carved out. The path leads to the village and St. Declan’s holy well.

Remnants of by-gone spiritual hunger and discovery still cling to the old ruins at Ardmore. The stones hold the memories of faith, of sorrow, of devastation, of joy, of celebration. It is the presence of those memories stored in the ruins that dissolves the veil separating the past, present and eternal worlds. All are knitted together and the elements – the sky, the wind, the sea, the stones – seem brighter, and somehow more vivid.

Ardmore is a thin place, and is on our Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland this September. Come join us.