St. Gobnait’s Holy Well – Ballyvourney

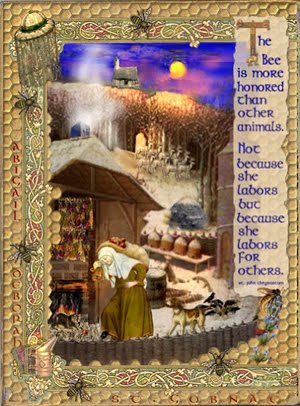

St. Gobnait – image by Patricia Banker

In the early 6th century when Gobnait fled her home in County Clare, she went to Inis Oírr. We don’t know why she fled, only that she believed she would find refuge in the Aran Islands.

Legend states that an angel appeared to her there and told her that her place was not on Inis Oírr, and instructed Gobnait to go on a journey – to seek her true place of resurrection. “Go until you find nine white deer grazing” the angel told her. “It is there that you will find your place of resurrection.”

So Gobnait wandered about the southern coastal counties of Ireland – Waterford, Cork and Kerry – searching.

She saw three white deer in Clondrohid and followed them to Ballymakeera where she saw six more. But it wasn’t until she came to Ballyvourney to a small rise overlooking the River Sullane that she saw the nine white deer all together – grazing … just as the angel from Inis Oírr had prophesied.

She crossed the river and settled there. She founded a religious community for women, performed memorable – some say miraculous works, and it was there she died and was buried.

Thin Places Mystical Tour

St. Gobnait’s shrine and holy well are stops on our Places of Resurrection tour .

DEVOTION TO ST. GOBNAIT

February 11th is St. Gobnait’s feast day -the day her memorable life is celebrated. She is one of the few Irish saints that is not only remembered in her native region, but has been proclaimed by the Irish bishops to be a national saint. There are shrines and places of devotion to St. Gobnait in all the places she is believed to have stopped on her journey – including Inis Oírr. But Ballyvourney, where she carried out most of her ministry, is the place that draws the greatest number of pilgrims devoted to this saint.

Today there is an active church on the former monastic site. St. Gobnait’s grave and marked spots around the churchyard are places where pilgrims pause for devotion and reflection. It is here that they can do the “rounds” or turas, always moving in a clockwise direction – a tradition that has pagan roots.

One of the strongest mystical draws on this site is St. Gobnait’s Holy Well, with its arched entryway that takes the pilgrim into a deeply shaded path. Just next to the well is a sturdy tree, and hanging from it are hundreds of tokens or clooties that have been placed there by pilgrims hoping to leave behind a part of themselves or loved on in need of healing. There are taps and cups available for drinking from the well or for pouring into personal vessels to take holy well water home.

Entrance to St. Gobnait’s Holy Well

St. Gobnait was best known for her care of the sick. There is a legend that tells of her staving off the plague from Ballyvourney by drawing a line in sand with a stick and declaring the village “consecrated ground.” Inside the church today, there is a medieval (possibly 13th century) figure of St. Gobnait which is kept in a drawer. Every year on her feast day, the parish priest brings out the figure to celebrate a devotional tradition. He holds up the ancient figure and the faithful each step forward with a piece of ribbon. They hold the ribbon up and measure it against the length and around the circumference of the figure, then take it home as a blessed relic used for healing or further devotion.

A tall statue of St. Gobnait that was erected in the 1950s stands near the monastic site. She appears with a nun’s habit standing on a bee hive surrounded by bees. Gobnait is the patron saint of bee keepers, and there are several legends recalling Gobnait forcing invaders out of Ballyvourney by setting swarms of bees upon them. It’s probable that Gobnait had a close relationship with bees and used honey in healing efforts.

Statue of St. Gobnait at Ballyvourney

PLACE OF RESURRECTION

Dan and I visited St. Gobnait’s monastic site many years ago. It is indeed, a thin place. The stories of St. Gobnait specifically mention a “place of resurrection.” I heard Dara Molloy use this phrase when referring to his home on Inis Mór and have seen a few authors reference the phrase. But regarding thin places … a place of resurrection is the pinnacle – that place where one’s spirit is totally whole, at home, with no longing or yearning to be anywhere else. A place of resurrection is not only the place where one’s spirit will resurrect from its lifeless body upon death, but also the place where that spirit is most alive inside the living body. And I believe that a place of resurrection is the spiritual home where one is most completely alive and able to create, to discern, to prophesy … to be wise.

Tree at St. Gobnait’s Holy Well – Ballyvourney, Co. Cork

The connection between the eternal world and the physical is nearly unidentifiable in a place of resurrection – as they are knitted together in an inextricable pattern where neither can be separated from the other. The place of resurrection then is unto itself the combination of both worlds particularly suited to that specific spirit. … and Ballyvourney was St. Gobnait’s place.

What is yours?

Image of St. Gobnait courtesy of Patricia Banker; Copyright by Patricia Banker, All Rights Reserved. Used With Permission.

Timoleague – Mystical Ruin on the Sea

Along the road between Kinsale and Clonakilty, near Courtmacsherry is the village of Timoleague which is dominated by the great seaside abbey ruin, a remnant of a 13th century Franciscan Friary. The abbey is built on the site of a former monastery founded by St. Molaga in the 7th century. Timoleague means – “house of Molaga.”

St. Molaga, as the story goes was a local boy who went to study the rule of St. Columba in Iona and then went on to Wales where he became good friends with St. David. He returned to Ireland and founded several monastic communities, but Timoleague was his greatest – and his last. He died here – probably of the plague. He and his followers were committed to helping those suffering from the disease when the plague hit Ireland in the late 7th century.

A story is told about how St. Molaga originally wanted to build his monastery farther up the estuary. But as he and his followers labored on the buildings by day, they all collapsed by night. St. Molaga took this as a sign that the Lord did not approve of the location. So he blessed a candle, lodged it in a rolled up sheath, set it alight and released it on the bay praying that God would help him find the perfect location for his new religious community. The candle floated until it stopped at the where the Timoleague ruin now stands. St. Molaga built his monastery on the sea and six hundred years later the Franciscans built an abbey on the foundations of St. Molaga’s monastery. The ruins of that monastery are what visitor’s see today.

I found this thin place through the recommendation of Mr. Noel O’Connor who was my host at Ashgrove Bed and Breakfast in Bandon. Over breakfast I asked him, “What is the most mystical place around here?” He was caught off-guard and hesitated. As a forma garda (police officer) I suspect he wasn’t invited to discuss “mystical” or thin places often. After pausing to give it some thought, he told me that many pilgrims go to Timoleague to pray and reflect. So I took his advise and I went to Timoleague.

What remains is a beautiful ruin now made into a comfortable public space on the scenic Courtmacsherry Harbor. When the monastery was active, boats used to sail right up to abbey, and the village grew around the activities focused there. Past the picnic tables and the stone wall are bones of the old religious house with haunting traces of how life existed there so many years ago.

Two favorite spaces for me were the dining room and the cloister walk. Pictured above is the cloister garth the part of a corner wall still standing. Monasteries typically had these square cloister walks with an open court-yard type garth in the center. The walks were the center of the the cloister and often used for doing “rounds” or walking and praying in a circular path. The walls bordering the garth had gothic-style windows to look out. I love to trace the steps of those who once walked and prayed here. On account I read said that at one corner of the walk the incorrupt body of a monk buried centuries before was discovered. He was reinterred on the grounds.

Another peaceful spot here is the refectory or dining area. It’s a large rectangular room off the back of the ruin with five tall windows (frames still in tact) looking out over the sea. Next to this area is a cavity wall, with indentations known as the fairy cupboards. It was from this room that children discovered an ancient book buried under one of the flagstones. They destroyed it and only the shred of the cover was found.

In the sacristy is the ancient holy water font, now known as the Wart Well. It is said to heal warts when those afflicted dip the warts into the water.

The monastery was sacked in the 1600s and three monks escaped by boat and took with them the Timoleague chalice for safe keeping. It was discovered in an old box in a home in the village many years ago and is now held by one of the priests residing in Timoleague.

In the distance behind the ruin a round tower (new) can be seen atop a church. This is the Catholic Church dedicated to the Nativity of the Blessed Mother. One of Henry Clark’s last stain glass masterpieces can be found here.

Timoleague is a haunting site full of mystery and charged with the energy of the past. It is one of the stops on the Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland in May of 2011.

Holy House of ivied gables

That wert once the country’s pride

Houseless now in weary wandering

Roam your inmates far and wide

~from Lament Over the Ruins of the Abbey of Timoleague

John Collins -1814

Drombeg Stone Circle – County Cork

Drombeg Stone Circle – County Cork

The area in southwest Ireland – West Cork and much of Kerry – has over 100 prehistoric stone circles. What was the purpose of these circles and how were they used? One can only speculate. Reading the seasons, sacred worship, sacrificial offerings, astronomical clocks, burial grounds … these are just some of the uses the pre-Christian people of Ireland had for these stone circles. But there’s much more about the circles we still don’t know.

The circles in this region all have an odd number of stones. Drombeg has 13 – but it originally had 17. Most of the Cork / Kerry circles follow a specific astronomical orientation, having an axial stone (usually a lower, shorter stone in the circle) on the western edge opposite a set of entrance or portal stones (usually taller) on the eastern edge. The axial stone is also called the recumbent stone. In the photo above, the two portal stones are in the center of the photo and the lower, axial stone can be seen between them on the opposite side of the circle.

A Winter Solstice Light Show

You can barely see the little notch in the hills behind the circle, but the hills define a sort of “V” on the horizon. On the winter solstice (Dec 21 – the shortest day of the year), the sun dips just under the ridge of that V in the hills, but as the earth moves the sun comes into the V in near perfect alignment with the axial and entrance stones – shooting its concentrated rays directly across the center of the circle. Accounts by people who have seen this process state that it looks as if for a few moments, the circle itself is illuminated independently of the surrounding landscape.

Why would this process have been important to these ancient people?

The Ridge is Man-Made

Excavations around the site back in the 1950s showed buried human cremated bones near the center of the circle coupled with broken pottery shards and stones. There were other burial pits near the circle with the same combination. Oddly, the shards of pottery and the stones seemed to be as revered in burial as the human bones. Excavation also proved that the plateau where the circle rests (Drombeg means “small ridge”) is man made. The people who built this circle evidently leveled the land – or ridge – to affect the perfect winter solstice drama that occurred in the circle during sunset.

Prehistoric Huts Nearby

In the same complex, near the stone circle are the remains of two prehistoric huts that were probably used for cooking – what we might call a “commercial kitchen” today. One of the huts had a capacity to boil about 70 gallons of water. Hot rocks from a fire were placed into a rectangular stone basin and within 20 minutes the water would come to a boil and remain hot for about 3 hours. This was probably how the ancient people boiled their meat. Remains of what was probably an oven are in the second circular hut. This tells us that the area wasn’t just a place to read the seasons or practice sacred ritual. The circle would have been a place of community.

The Drombeg complex is located between Skibbereen and Kinsale, and is easy to access with parking relatively close to the site. My first visit to Drombeg was in February of 2007. It was a cold, dreary, rainy day. I arrived tired. It was my last site of the day. The time was 5:00 pm. As I approached the site from the car park, I was unimpressed at first. The site seemed to have no sense of place. In fact, save for the shadows from the stone circle, the site looked like another farm field with houses nearby.

But as I walked into the complex and took in the surroundings, the place became magical. This is a site worth visiting. Take some time to gather your senses about you and notice everything about the surroundings – the distant hills, the views of the sea, the sounds, the light, the stones themselves. Then when your sensitivities are peaked, enter the circle through the Portal stone entrance.

The following is from my travel journal which is mostly transcribed recordings of impressions I dictated into a digital recorder during the visit.

I take back what I said about this site being unimpressive. The stone circle is beautiful. It’s in a big clearing where the entire valley just unfolds as you approach the circle. And there are views of the sea – the Celtic Sea.

There are hills and hills of green. Expansive sky. It’s a big wide area. It’s a beautiful stone circle. The stones are thick and tall.

Walking through the entrance of the Drombeg portal stones is pretty powerful. You walk in through the center and you can feel it. There’s just something sacred about the center of the circle.. I noticed the axial stone had two notches. There is energy here. Old energy. Ancient energy.

Drombeg Stone Circle is a very thin place. It is one of the stops on the Thin Places Mystical Tour of Ireland – May 15 – 24, 2011. Full Tour Itinerary. Make your reservations today.

Skibbereen Famine Cemetery – a thin place

Abbeystrewery Cemetery in Skibbereen. 8000 – 10,000 victims of the Great Hunger are buried here.

Abbeystrewery Cemetery in Skibbereen. 8000 – 10,000 victims of the Great Hunger are buried here.

Skibbereen was a hub of commerce in southern Ireland during the nineteenth century, with the River Ilen flowing through the town ending at the Baltimore Harbour near the Atlantic Ocean. But Skibbereen is perhaps most famous for its association with the Great Famine that hit Ireland hardest in 1846-47. The song Skibbereenwith a haunting melody and lyrics that tell of a father recounting to his son the cruel reason why he left his beloved homeland “old Skibbereen,” – he lost the farm, the house, and he lost his wife to hunger when the boy was but 2 years old. So the father fled with the young son wrapped in his coat – never to return for fear of being imprisoned for the debt he owned in taxes and rent. County Cork was one of the areas in Ireland that lost over one third of its population to the Famine in those years.

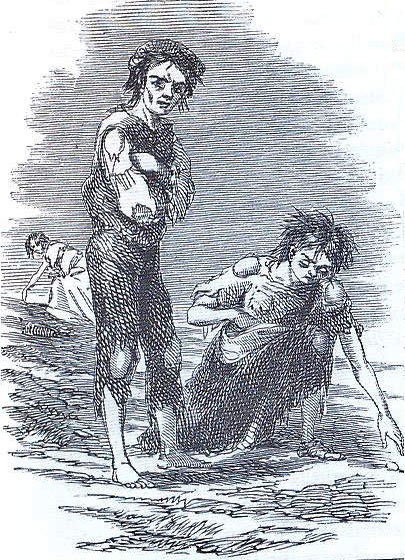

History states that the Famine occurred because of a failure in the potato crop in Ireland. The Irish were under British occupation at the time. Rich landlords controlled the country, though they were a small portion of the population. Most of the population served as tenants to these landlords, and suffered from high rents and taxes. Poverty ran deep in the tenant class, which used the potato as the main staple of its diet. When the crop failed, panic set in. The Irish sold what they had, including boats and fishing equipment to feed their suffering families. One in three people died in the area surrounding Skibbereen. Most concur that there was plenty of food in Ireland – plenty enough to feed the starving citizens. But the food was exported for profit that was made by the British government and the Anglo Irish ruling class.

Sketch by illustrator James Mahony entitled – Skibbereen 1847 – Mahony produced this for a London newspaper in the same year

Sketch by illustrator James Mahony entitled – Skibbereen 1847 – Mahony produced this for a London newspaper in the same year

People were dying so fast in Skibbereen that there weren’t enough people alive to take care of the task of burying the dead. So a mass grave was dug near the ruins of the old Abbeystrewery Franciscan friary. It is estimated that 8,000 to 10,000 nameless, coffinless, unremembered dead were dumped into the mass grave. Today the lumpy plot of ground has green grass covering the burial site and a stone marker that says:

In Memory of the Victims of the Famine 1845-48

Whose Coffinless Bodies were Buried in this Plot

There is a commemorative Famine trail that begins at the town center and includes the Skibbereen Heritage Centre and the Abbeystrewery Cemetery (pictured above). The artistic renderings of stone cutters and poets that dapple the cemetery grounds with tokens of remembrance are worth a trip to Skibbereen. So much sorrow here. One can’t helped but be moved.

Skibbereen is a thin place. And it is a stop on our Thin Places Tour in September 2010.